Karen Wetterhahn

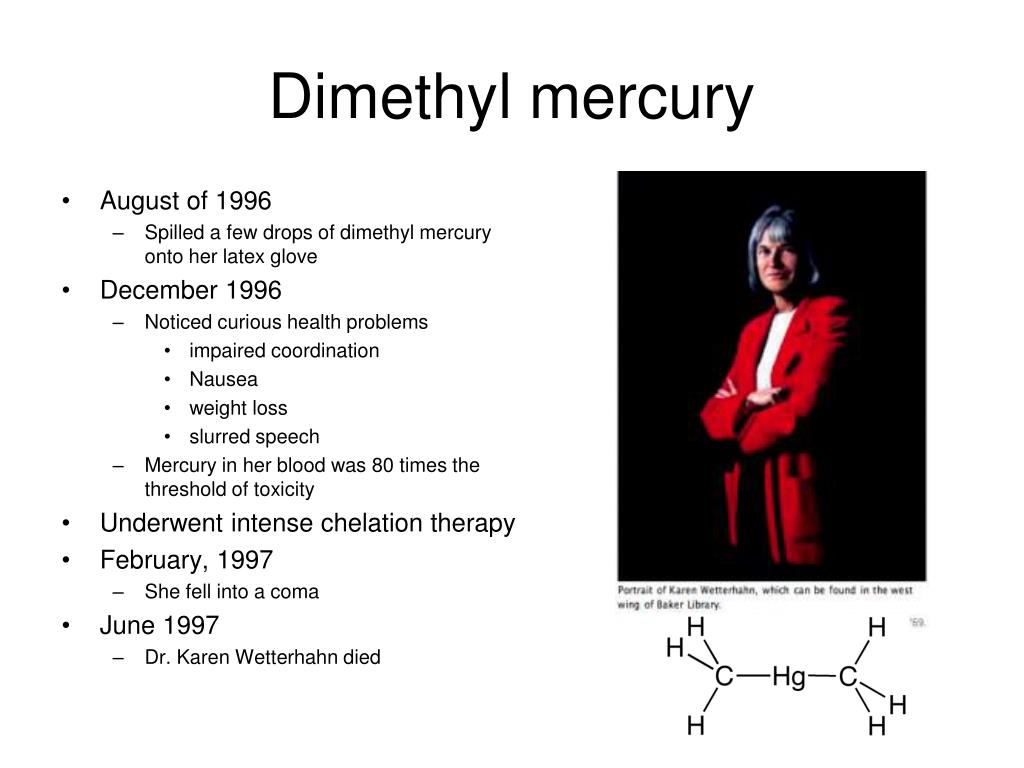

Karen Wetterhahn was pipetting a small amount of dimethylmercury under a fume hood in her lab at Dartmouth College when she accidentally spilled a drop or two of the colorless liquid on her latex glove.

The chemistry professor and toxic metals expert immediately followed safety protocol, washing her hands and cleaning her tools, but the damage was already done, even though she didn't know it.

In November 1996, Karen began vomiting and feeling nauseous. Over the next couple of months, her condition worsened; her speech was slurred, she had trouble seeing and hearing, and she was regularly falling down.

At first, doctors in the emergency room didn’t know what was wrong. After a series of spinal taps and CT scans, doctors told Karen her symptoms were consistent with mercury poisoning.

Karen told them about the dimethylmercury spill in her office. She was diagnosed with mercury poisoning in late January 1997 and soon after began chelation therapy, ingesting medication that would bind to the toxic chemical and help it pass through her body.

While Karen was fighting for her life, her colleagues at Dartmouth (as well as scientists around the world) read scientific papers about mercury, hoping to discover a way to help her. They also tested her hair, clothing, car, students, family, and hospital room to make sure that no one else had been exposed to dimethylmercury.

Sadly, the level of mercury in Wetterhahn’s blood was too high—800 times the normal level—for doctors to save her.

She went into a coma in February, and died on June 8, 1997.

Scientists would later learn that Karen’s latex gloves offered no protection from the dimethylmercury, an especially dangerous organic mercury compound.

Although a few other people had died from dimethylmercury poisoning before, including English lab workers in 1865 and a Czech chemist in 1972, no one understood how dangerous the substance really was.

Karen’s death would change that and usher in new safety standards for one of the most toxic substances known to humans.

SPREAD THE WORD. RAISE AWARENESS ABOUT RISKS IN THE BIOTECH INDUSTRY.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance the understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific and social justice issues. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes.